Mitochondrial medicine takes a different angle on the study and treatment of chronic diseases like Type II diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). There is also some interesting work underway regarding mitochondria and the brain.

You may remember from high school biology class that mitochondria are the subunits of our cells (with the notable exception of our red blood cells), responsible for the production of chemical energy (ATP, or adenosine triphosphate) in our bodies.

A growing body of research now suggests that Type II diabetes and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease are not only strongly associated with, but are caused by, mitochondrial dysfunction. Mitochondrial medicine may provide a “grand unifying theory” of multiple effects, including insulin resistance and the reduced pancreas beta cell production.

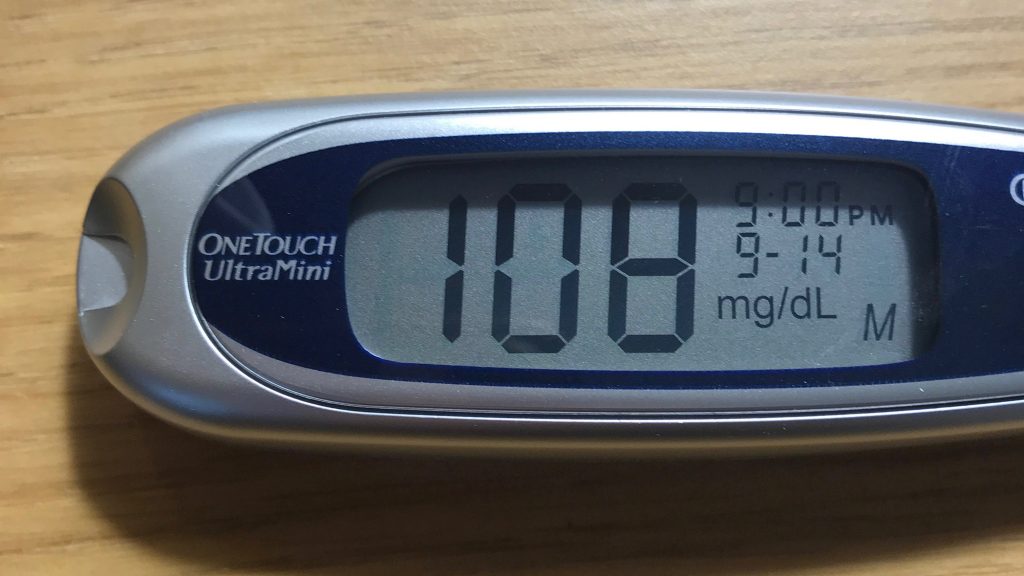

Maintenance of normal blood glucose levels depends on a complex interplay between the insulin responsiveness of skeletal muscle and liver and glucose-stimulated insulin secretion by pancreatic β cells. Defects in the former are responsible for insulin resistance, and defects in the latter are responsible for progression to hyperglycemia. Emerging evidence supports the potentially unifying hypothesis that both of these prominent features of type 2 diabetes are caused by mitochondrial dysfunction.

— “Mitochrondrial Dysfunction and Type 2 Diabetes,” Science, 21-Jan-2005, p. 384

In addition, “accumulating evidence indicate that hepatic mitochondrial dysfunction is crucial to the pathogenesis of NAFLD.”

The literature can get pretty technical surrounding the underlying mechanisms of the energy production, the impact on our organs, and our overall health. However, the root of the problems seem to stem from interruptions in the flow of electrons (often caused by oxidative stress) in a chain of reactions. I encourage any fellow geeks to read the underlying articles.

However, the purpose of this blog is to really summarize what’s happening in the observable “real world” to cause mitochondrial dysfunction and what we can do about it.

What Causes Mitochondrial Dysfunction?

Mitochondria are inherited from the mother, so if children are born with defective genes, they will generally see the onset of these symptoms in childhood.

However, it is very possible (and common) to acquire mitochondrial dysfunction in adulthood through oxidative stress. What has mitochondrial medicine deduced about causes for this oxidative stress and resultant mitochondrial dysfunction?

- Too much (or too little) physical exercise

- Unhealthy nutrition; lack of micronutrients; too many carbohyrdates

- Infectious diseases (viruses, bacteria)

- Environmental toxins, heavy medicals, chemicals

- Medications like cholesterol lowering drugs which cause reductions CoQ10, an important cofactor to mitochondrial function

- Antibiotics (mitochondria are like primitive bacteria!)

- Alcohol (through loss of B vitamins, zinc, magnesium, and biotin)

- Smoking (a direct oxidative stress)

- Physical trauma

The good news is that there are many mechanisms from nature that protect us from oxidative stress, including enzyme reactions involving antioxidants and that increase energy production, as well as natural substances that detoxify the body.

How can we prevent mitochondrial dysfunction?

Fasting

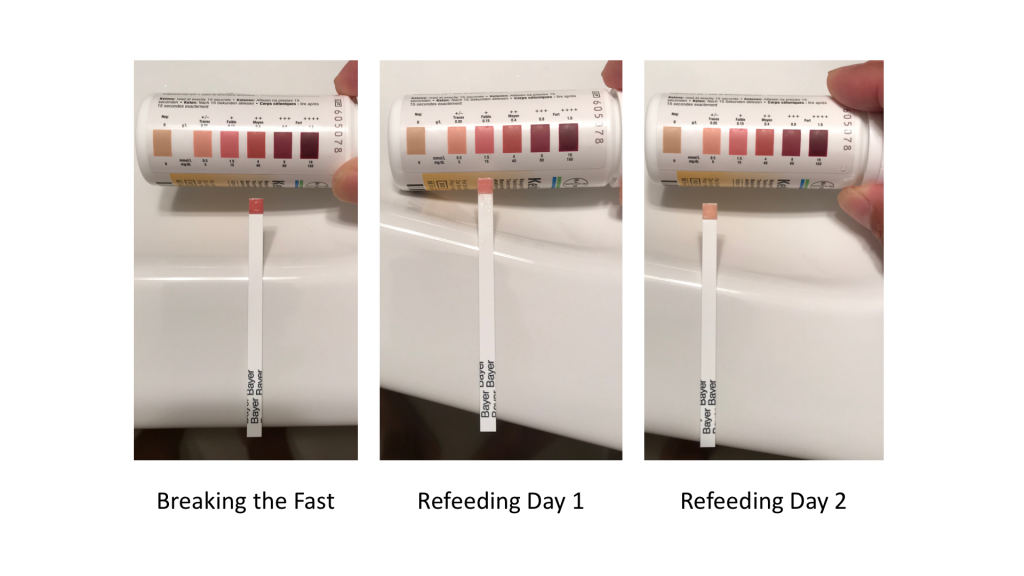

The “go to” treatment for mitochondrial dysfunction is fasting. Fasting for more than 12 hours without eating starts autophagy, or reparation of cells. It also spurs mitophagy, which is the decomposition of damaged or defective mitochondria, key to restoring proper mitochondrial function.

In addition to metabolic benefits, fasting is also beneficial for the brain. Fasting for prolonged periods triggers ketosis. For the brain, using ketone bodies for fuel helps to produce more energy than the glucose branch and produces less oxidative stress. In prolonged fasting, the brain can consume 2/3 of its energy from ketone bodies and reduce its glucose consumption to 1/3 (per a 2005 study).

Prolonged fasting has been shown to help regenerate the mitochondria (and the neurotransmitters!) inside the brain. Mark Mattson, Chief of the Laboratory of Neurosciences at the National Institute on Aging, did an informative TEDx talk on how intermittent fasting helps the brain through improving mitochondrial function.

Moderate physical exercise

Moderate physical exercise stimulates production of the body’s own antioxidants and growth of mitochrondria in skeletal and heart muscles. Be careful, though. Too much exercise has been shown to have the reverse effect. For reference, see the abstract for a 2005 paper aptly titled “A half-marathon and a marathon run induce oxidative DNA damage, reduce antioxidant capacity to protect DNA against damage and modify immune function in hobby runners.“)

Relaxation techniques

Every day our brains burn 600 calories – 1/3 of our total energy expenditure!

Relaxation techniques, such as meditation, have been shown to reduce this energy expenditure, resulting in less mental stress, less oxidative stress, nitrosative stress and inflammation. These relaxation techniques also promote regeneration of enzymes, better metabolic efficiency, and production of hormones like serotonin.

Micronutrients

There are two categories of micronutrients to take. Academic papers (example) list many of these micronutrients that can support mitochondrial function.

- Reduce oxidative stress

Vitamin C, Vitamin E, Reduced Glutathione, CoQ10, Vitamin B2, Omega 3 fatty acids, Zinc, Manganese, Copper, Selenium, Curcumin (turmeric), Silymarin (milk thistle), Provitamin A Carotenoids, Reservatrol (grapes), Quercetin (apples), et al - Promote energy production

Vitamin B1, Alpha Lipoid Acid, Vitamin B2 and Vitamin B3, Magnesium, CoQ10

Elimination / Detoxification

The aim of “elimination” is to absorb toxins within the gastrointestinal tract, again to improve mitochondrial function.

Some substances that have been investigated to help eliminate toxins include:

- Chlorella algae (our family favorite, which we have been taking for 15 years!)

- Zeolites – powdered volcanic stone

- Healing earth / medical clay

- Apple / citrus pectin

Summary

The net here is that the mechanisms and scientific foundations explained by mitochondrial medicine call for treatment using many of the same techniques as those evangelized by today’s complementary or alternative therapies — including fasting, exercise, relaxation, and detoxification supplemented with hgh quality micronutrients. The difference now is that mitochondrial medicine is beginning to scientifically explain and study what many of the “natural healing” practitioners have already been practicing for years!