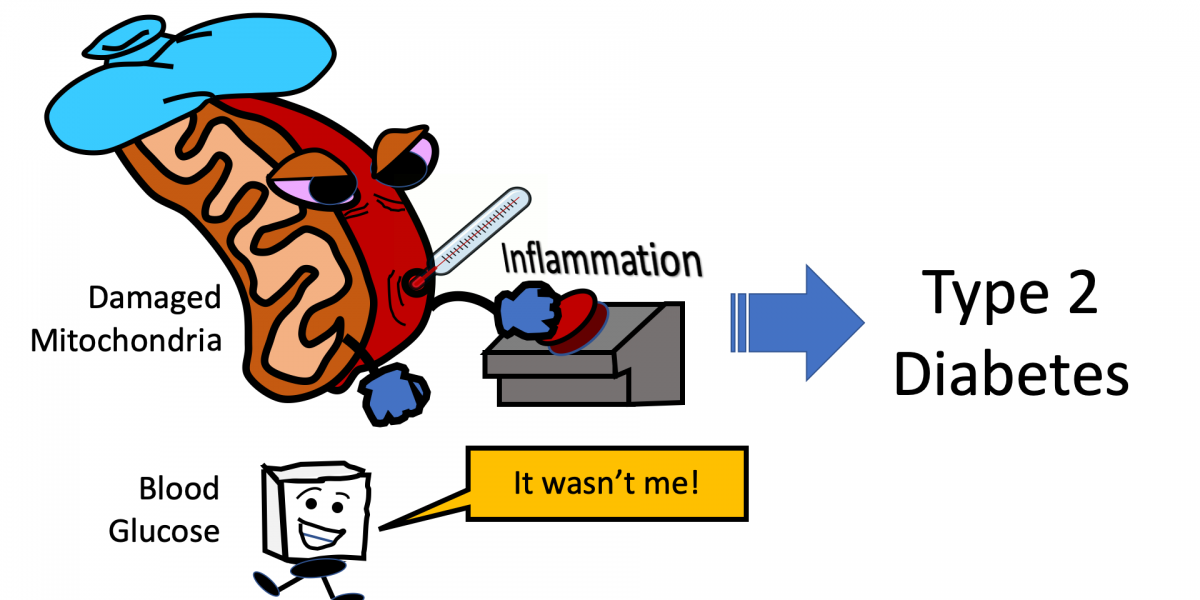

There has been a long-standing belief that consuming too much sugar was the cause of Type 2 diabetes and that treating diabetes was about controlling blood sugar. Makes sense, right? Well, it’s more complicated.

Recent research has now provided evidence that mitochondrial dysfunction (previously covered on this blog) — involving fats, not glucose — may be to blame for the inflammation which causes type 2 diabetes!

Warning: In no means does this post advocate any stoppage of treatment for blood glucose control. The recent research just reveals that there is more to the story.

Inflammation and Type 2 Diabetes

For context, it has long been demonstrated that there is an association between inflammation and the onset of Type 2 diabetes. A 2001 study published in JAMA stated the following:

Our epidemiological observations, coupled with emerging experimental evidence, support a possible role for inflammation in the pathogenesis of type 2 DM. Our data also raise the possibility that inflammatory markers, like CRP, might provide an adjunctive method for early detection of risk for this disease.

As research progressed, refined conclusions made their way from research publications into the popular press. A Scientific American article from 2009 described this phenomenon:

Researchers have since shown that TNF-alpha—and, more generally, inflammation—activates and increases the expression of several proteins that suppress insulin-signaling pathways, making the human body less responsive to insulin and increasing the risk for insulin resistance.

This phenomenon was summed up well in a review of a 2014 study where the editor of the Journal of Leukocyte Biology wrote:

The more researchers learn about obesity and type 2 diabetes, the more it appears that inflammation plays a critical role in the progression and severity of these conditions.

The real question then was what causes the damaging inflammation?

Understanding the Cause of the Inflammation

It has been assumed that high blood sugar levels were to blame for this inflammation in diabetic patients and that achieving healthier blood sugar levels was the key to reducing inflammation. However, the recent study cited earlier challenges this assumption.

With the initial assumption that glucose caused the inflammation, the researchers Barbara Nikolajczyk from University of Kentucky and Douglas Lauffenberger from MIT hypothesized that immune cells from patients with type 2 diabetes would produce energy by burning glucose. The team was surprised to find that glycolysis, a reaction involving glucose for other types of inflammation, was not driving chronic inflammation in diabetic patients. Instead, a combination of defects in mitochondria and elevated fat derivatives were responsible.

Solving a Long-Known Mystery

One long-known mystery in diabetes control emanated from the ACCORD (Action to Control Cardiovascular Risk in Diabetes) study back in 2008. It compared intensive therapy (HbA1C levels below 6.0%, similar to a non-diabetic patient) with standard therapy (HbA1C levels between 7.0% and 7.9%). The conclusion was surprising in that mortality rates increased with tighter blood glucose control.

As compared with standard therapy, the use of intensive therapy to target normal glycated hemoglobin levels for 3.5 years increased mortality and did not significantly reduce major cardiovascular events. These findings identify a previously unrecognized harm of intensive glucose lowering in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes.

This increase in mortality ultimately resulted in the early halting of the glucose-control arm of the ACCORD trial.

A follow-on study to ACCORD (ACCORDION) invited all surviving ACCORD participants who were later treated according to their health care provider’s judgement. Once their data was collected, the study revealed that the period of intensive treatment during ACCORD did not help in the long-run.

In high-risk people with type 2 diabetes monitored for 9 years, a mean of 3.7 years of intensive glycemic control had a neutral effect on death and nonfatal cardiovascular events but increased cardiovascular-related death.

While there was well-documented analysis on ACCORD and ACCORDION, there remained a mystery of exactly why lowering blood glucose back to normal levels didn’t produce the desired effects. This latest study may begin to unravel some of the mystery.

As noted by the study authors…

“Our data provide an explanation for why people with tight glucose control can nonetheless have disease progression.” – Barbara Nikolajczyk, Ph.D, UK Barnstable Brown Diabetes Center https://t.co/RPNh0wY7PT

— UK HealthCare (@UK_HealthCare) August 31, 2019