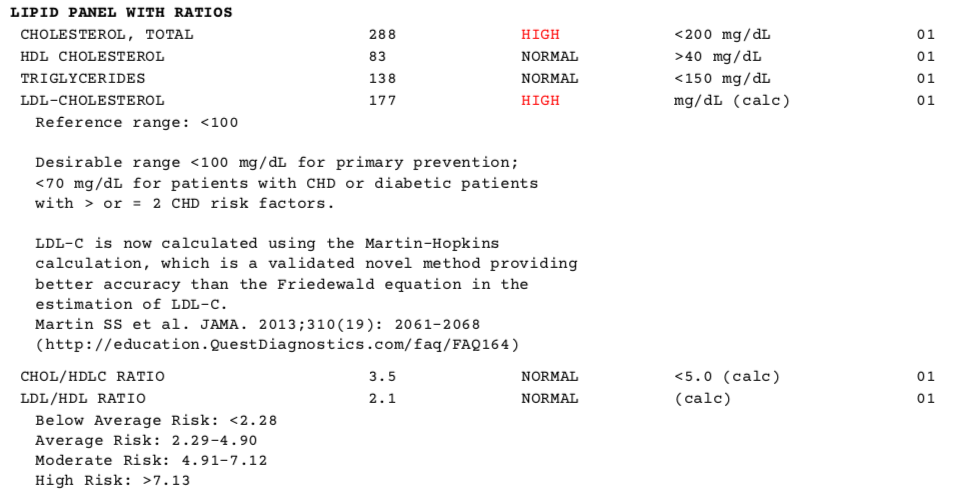

Do you have high LDL or high total cholesterol? If you read my previous article about cheese, you may recall that these LDL or total cholesterol numbers alone are not reliable predictors of mortality from heart disease.

An NBC News piece went further to cite American science writer Gary Taubes who reported that the LDL and total cholesterol numbers have been such poor predictors of disease risk that early screening tests should have likely just tested for HDL and triglycerides and nothing else.

A 1977 NIH study — an early set of papers from the now legendary Framingham Heart Study — confirmed that high HDL is associated with a reduced risk of heart disease. It also confirmed that LDL and “total cholesterol” tells us little about the risk of having a heart attack, language that heart-disease authorities would downplay years later. Given this finding, as Gary Taubes writes in “Good Calories, Bad Calories,” we would have been better off to start testing for HDL — or even triglycerides — and nothing else.

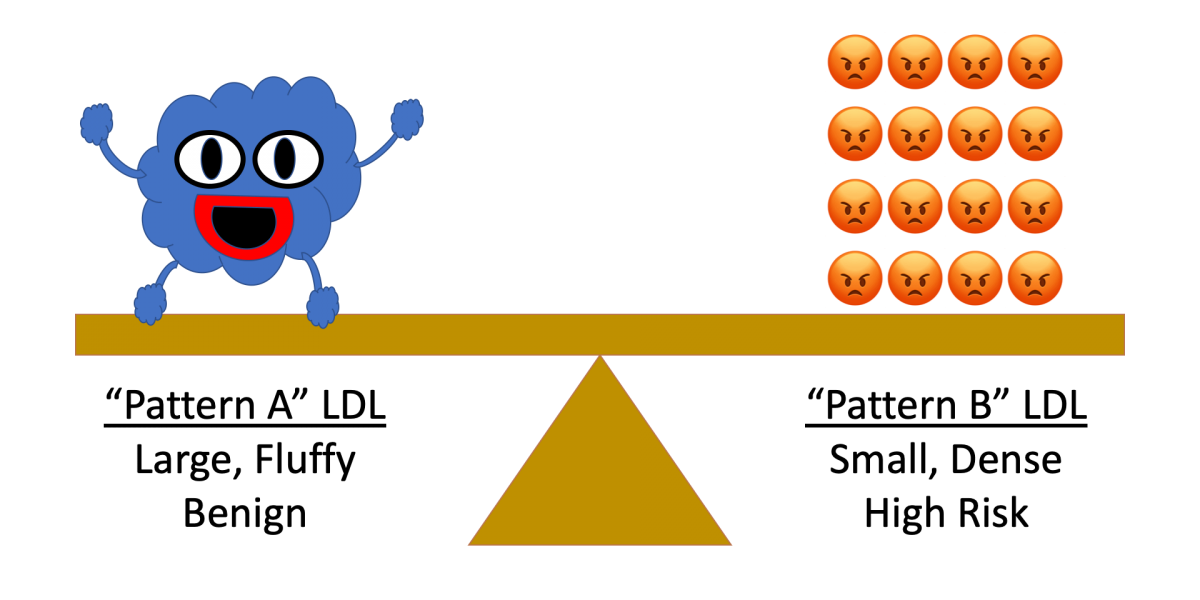

A more nuanced view associates the risk of atherosclerosis and heart disease with the type of LDL particles. There are two patterns (also referred to as “phenotypes”) of LDL particles.

- Pattern A: large, fluffy LDL particles which are largely benign

- Pattern B: small, dense LDL particles which are more likely to oxidize and lodge themselves to arterial walls

Studies have long shown the impact of LDL particle size on disease risk. A 1988 study in the Journal of the American Medical Association documented the association between Pattern B (small, dense) particles and disease risk:

The LDL subclass pattern characterized by a preponderance of small, dense LDL particles was significantly associated with a threefold increased risk of myocardial infarction, independent of age, sex, and relative weight.

So why not test for LDL particle size? The tests are more expensive!

However, there is an answer. While testing for LDL particle size is more expensive today than commonly used cholesterol tests, a triglyceride / HDL ratio of 3.8 or higher can predict pattern B with high confidence. A 1997 Harvard Medical School study also confirmed the efficacy of triglyceride / HDL ratio to predict the risk of myocardial infarction.

Given the age of these studies, the use of HDL and triglycerides has become accepted practice in some circles, as described by Everyday Health.

According to Scott W. Shurmur, MD, the medical director of the cardiovascular center at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center in Lubbock, Texas, the particle test should be used for people who have other risk factors for heart disease or stroke, such as a family history of heart disease at early ages. “At the same time, standard cholesterol tests like HDL and triglycerides provide similar information (and are less expensive), particularly if non-HDL cholesterol is incorporated into the assessment,” says Dr. Shurmur.

Unfortunately, there are no widely adopted standards today for metrics of triglyceride / HDL ratios in common clinical practice. Some researchers have provided guidelines, including Zone Diet creator Dr. Barry Sears who wrote:

How can you tell which type of LDL you have? All you have to do is determine your ratio of triglycerides to HDL cholesterol, which would be found as part of the results of your last cholesterol screening. If you ratio is less than 2, you have predominantly large, fluffy LDL particles that are not going to do you much harm. If your ratio is greater than 4, you have a lot of small, dense LDL particles that can accelerate the development of atherosclerotic plaques – regardless of your total cholesterol levels.

Still, patients who view their standard lab test results will notice that standard lab results list other ratios including Total Cholesterol / HDL and LDL / HDL ratios, but they do not list Triglyceride / HDL ratios.

(TG/HDL = 138/83 = 1.7)

So why aren’t Triglyceride / HDL ratios more in use, or why aren’t LDL particle sizes discussed more often in the doctor’s office? After all, most of the research cited in this blog article is decades old!

Frequent readers of this blog know my skepticism around a lot of Western Medicine. Most continuing education for doctors is sponsored by pharmaceutical companies who have commercial interests in promoting use of lab numbers that their drugs can lower! According to an academic paper titled “Statins Do Not Decrease Small, Dense Low-Density Lipoprotein:”

Our study suggests that statin therapy—whether or not recipients have coronary artery disease—does not decrease the proportion of small, dense LDL among total LDL particles, but in fact increases it, while predictably reducing total LDL cholesterol, absolute amounts of small, dense LDL, and absolute amounts of large, buoyant LDL.

In other words, drug companies likely suppress the information about LDL particle sizes because their drugs preferentially target the benign “Pattern A” particles over the more harmful “Pattern B” particles!

My opinion: Before going on cholesterol lowering drugs, take a look at your triglyceride / HDL ratio. You may have “Pattern A” LDL particles and be at lower risk of heart disease than your LDL or total cholesterol numbers suggest.